The Normalized vs. The Noticed

True guardianship begins with acknowledging the subjective experience of the horse.

It is not unusual for a domesticated horse to be rugged. For Montana, whose history of severe allergic reactions to insect bites is a constant concern, a light mesh rug in the warmer months is not a luxury—it is an essential.

Recently, I replaced her old, imported hybrid rug with a high-quality "flag rug," a style widely accepted within equestrian culture as the standard for summer protection. Initially, the rug appeared to sit correctly, conforming to the standard silhouette of a well-fitted garment. Yet, within weeks, the 'normalized' became the 'noticed.'

Beyond the Instrumental

In my dance practice, I learned that the smallest restriction in a costume or a joint’s range of motion can compromise the integrity of the entire body’s alignment. In equitation, we often fall into "instrumentalisation"—providing the best vets, farriers, and feed, yet missing the subjective experience of the horse standing right in front of us.

The ISES paper, "But my horse is well cared for," explores how "enculturation" leads us to ignore these subtle welfare issues because "that’s how it’s always been done". It’s easy to employ "trivialization"—telling ourselves it’s just a small rub while the horse has a full belly. But true guardianship requires us to break away from these justifications.

Identifying the point where 'normalised' design becomes a source of physical discomfort.

The Psychology of Care

Definitions derived from Cheung, Mills, & Ventura (2025)

Enculturation: The social process of adopting a culture's unique attitudes and behaviours. In equestrianism, this can normalise welfare-compromising practices by passing them down through generations of trainers and coaches.

Cognitive Dissonance: The mental discomfort experienced when an individual’s beliefs (e.g., caring for a horse) conflict with their observations or actions (e.g., witnessing or performing harmful practices).

Trivialization: A dissonance-reduction strategy where one minimizes the importance of a welfare issue. For example, justifying a rub by comparing it to worse abuses or focusing on the horse's "good" life in other areas.

Instrumentalisation of Care: Providing care primarily to ensure a horse can fulfill its "job" or produce performance results. This distances the caregiver from the horse's subjective needs.

—————

Cheung E, Mills D, Ventura BA. “But my horse is well cared for”: A qualitative exploration of cognitive dissonance and enculturation in equestrian attitudes toward performance horses and their welfare. Animal Welfare. 2025;34:e50. doi:10.1017/awf.2025.10028

Keywords: Animal welfare; care ethics; cognitive dissonance; enculturation; horse welfare; performance horses

The Geometry of the Fix

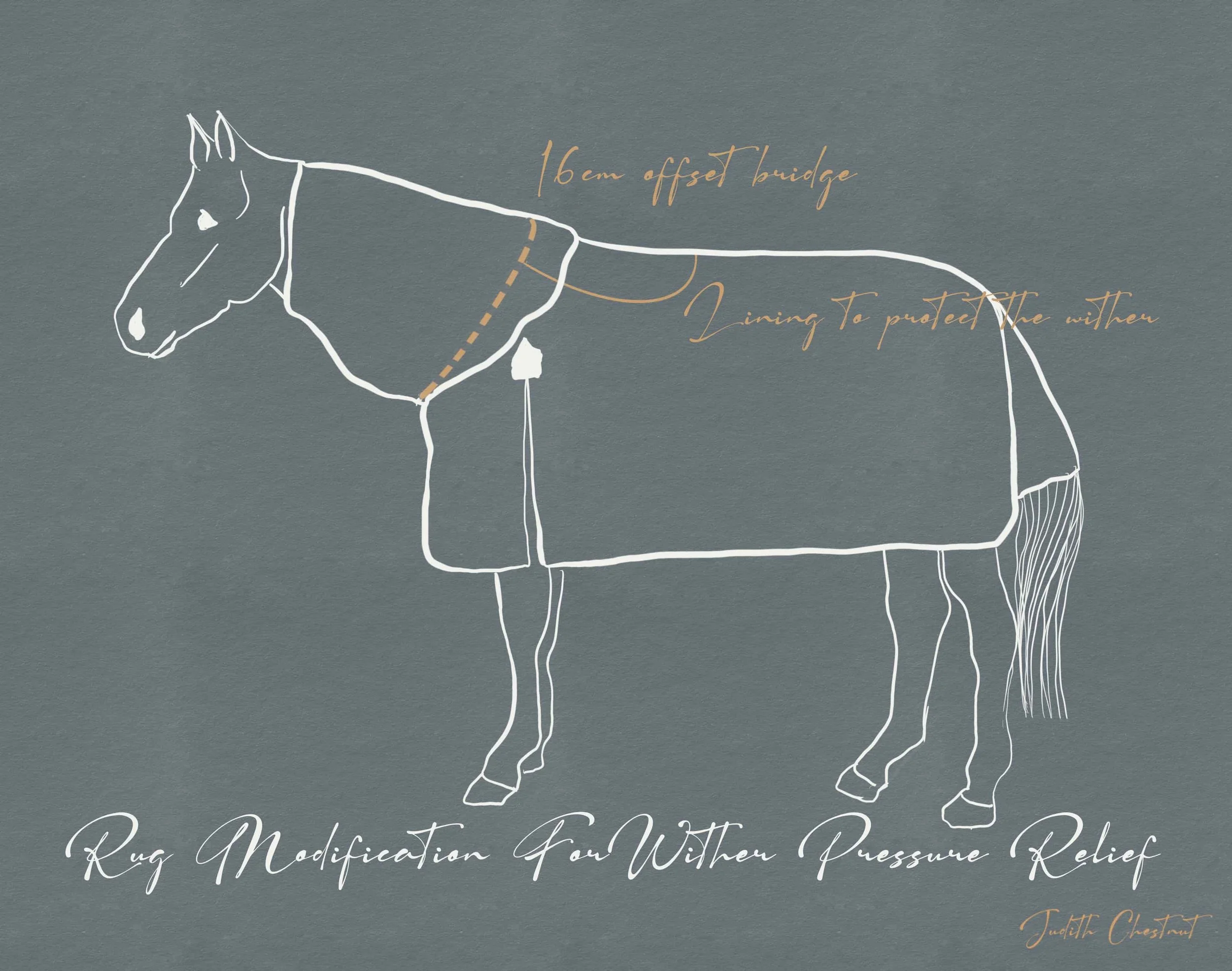

Upon closer inspection, I identified a classic structural design flaw. While her old rug featured an offset neck attachment, the new rug’s neck was sewn directly to the body, placing four layers of binding seams directly across the wither. Every time Montana lowered her head to graze, those seams acted as a saw.

This week, my studio practice shifted from the digital tablet to the sewing machine. Moving the neck seam forward by 16cm to create a "bridge" for the wither is a project requiring the precision of a Sumi-e stroke. It is more than a simple renovation; it is a refusal to accept a "normalised" discomfort and a commitment to Montana as a subjective partner whose comfort is the foundation of our trust.

Applying the precision of a Sumi-e stroke to the reality of horse care.

Coming Soon: The Technical Challenge In Part 2, I move from the digital tablet to the sewing machine. I will share the process of implementing the 16cm setback, the limitations of domestic equipment against industrial standards, and the results of Montana’s first trial in her redesigned gear. We will see if precision and intent can successfully overcome the 'normalised' flaws of design.